Vest Pockets

Charlotte learns that Doug’s voluminous vest pockets are more than a punchline

Previously on Between Corners: Doug’s volunteer work in the Grand Canyon reveals how high the stakes can be.

I tried not to laugh.

Douglas and I were at the South Kaibab trailhead. I felt a little special because his PSAR parking permit let us skip the crowded shuttle.

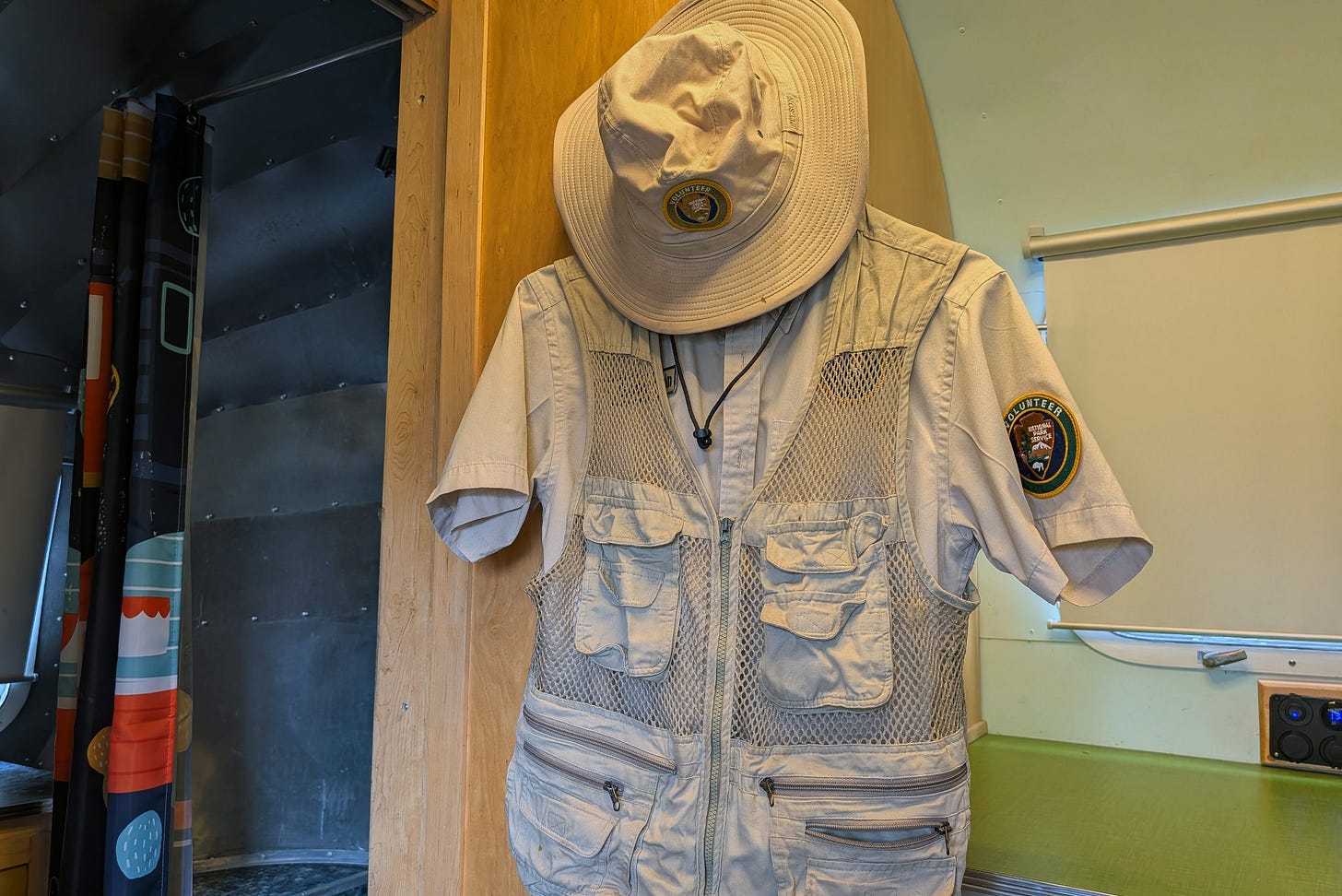

Then he started to put on his gear. Floppy hat with a “National Park Service Volunteer” logo. Radio. A tan mesh vest festooned with pockets.

I finally couldn’t help myself.

“Think you got enough pockets there, Ranger Douglas?” I asked him.

He looked at me, a little amused himself. “Well, I have lots of stuff to carry. I seem to recall the last time we were here I didn’t have enough. Not repeating that mistake.”

“No,” I said, remembering that incident. He had forgotten our snacks, and I had bonked hard. It was ugly. “That’s a good thing.”

And yet he looked like someone had picked up an REI store and dumped it on him.

“What does all that weigh?”

“I dunno. Thirty pounds. Thirty-five.”

I suddenly felt wimpy with my little daypack. Water, lunch, sunscreen, a windbreaker, spare sunglasses.

As we neared the top of the trail I heard his radio squawk. “Dispatch, Papa 49, in service…” he said.

Papa 49? How adorable.

He clipped the mic to his vest and extended his trekking poles.

“Ready?”

“Ready.”

I had forgotten the trail geography. We started down a series of switchbacks so steep I could look down three turns and see people seemingly directly below us. Then there was the striking view of the canyon, rendered almost telescopic because of the way two ridges narrowed my perspective.

Douglas described it as the most alien landscape on Earth. I was inclined to believe him.

Nonetheless, I had not really wanted to make this trip. In fact, I was more than a little annoyed when Douglas announced that he’d be away the first half of August. That left me with too much to do – managing my business as well as the ranch.

Then our dear neighbor, Jim Baker, let me know he and his wife Charmaine were around. Just in case. So, I relented and agreed to come out for four days. And as my flight into Phoenix touched down, I had to admit I was curious about what a volunteer like Douglas did. He talked about it all the time, but I hadn’t been able to really picture it.

And now that I could, it was starting to look like ranger cosplay.

Past the switchbacks the trail descended more gradually, along handsome little trees with deeply cut pale green leaves that Douglas said were Gambel oaks. It was shady here, cool enough that I stopped to take my windbreaker out of my pack.

I caught up to Douglas a few yards later. He was talking to a man and a woman in their 40s who had Italian accents. The man was tall and had a salt-and-pepper beard. The woman was of average height – dark hair, quite pretty, wearing shorts and a sleeveless shirt.

“…at least eight hours,” Douglas was saying.

“That long?” the man said, disappointed.

“To the Colorado and back, absolutely,” Doug went on. “And besides, once you get to Cedar Ridge the view doesn’t really improve as you descend.”

“Alright,” said the man, making that simple word sound lyrical. “That’s good to know. We’ll hike to Cedar Ridge and probably come back out.”

“Good call,” Doug said.

He handed his phone to me. “Get a picture.” Then he stood next to the woman. Not the man. She put her hand lightly on his shoulder and bent a knee toward him. She looked at Douglas and smiled. Find your own ranger, I thought.

Then, over the next mile I watched the pockets go to work. Douglas pulled two 500 mL water bottles out of his pack and filled the Nalgene bottle of a young man who was dry. Not long after, a woman was trying to call a friend on her wireless. “Battery’s dead,” she said to her companion. Another pocket, a disposable phone battery. Then a teenage girl eyeing a nasty blister on her heel. Yet another pocket. Spenco Second Skin.

I began to wonder what would pop out of a pocket next.

Maybe a helicopter.

But there was something else.

At home he was pretty quiet around people. Here he was a complete motormouth. It was as if the canyon opened up something in him. Geology. History. Climate. Mules versus horses. Trails and routes.

By noon, we reached Cedar Ridge, the scene of the crime a year earlier. This time, rather than rain, a hot sun now beat down on us, and I had stuffed my windbreaker into my day pack an hour ago. But I could see a dark thunderstorm across the canyon, its virga blotting out the canyon’s lowest 500 feet of pink granite and black schist. The basement rocks, Douglas called them. 1.7 billion years old.

“Will that hit us?” I asked of the storm.

Douglas shook his head. “Nah. Moving east.” He was right.

A few minutes later a string of six mules clumped up the trail, led by a tough-looking black-haired cowgirl wearing leather chaps, a plaid Western shirt, and a sweat-stained Stetson. She rode her big, dappled animal to a hitching post, secured it, then tied the others.

I walked over and caught her eye. “I have horses,” I said. “May I pet one of your mules?”

The cowgirl looked me over. “No.”

The Italian woman had touched Douglas’s shoulder. I wasn’t allowed to touch a mule.

Douglas was starting to pack up. He had overheard the exchange between me and the cowgirl and wore the slightest of smirks.

“Very funny,” I said.

“Well, it was. If I had known you were going to do that I would have stopped you.”

Then he pointed across the canyon. “I want to get a picture of that storm.”

We walked to a better vantage point.

“Gorgeous,” he said.

“It is,” I said.

Something usually comes after this.

I reached out to touch Douglas’s arm.

He gave me an odd look.

“What?”

Then he took the picture.

The hike up and out was hot. We were perhaps a mile from the rim when his radio came to life.

“Dispatch, Papa 49.”

Douglas keyed his mic. “Papa 49.”

“Papa 49, some hikers called to tell us there is a young woman who is ill near the bottom of the switchbacks.”

Douglas scanned the trail above. “Copy that, dispatch. ETA to subject 20 minutes.”

“Copy, Papa 49.”

He clipped the mic to his vest and looked at me. “Take your time,” he said. “I need to hump it a little.”

He was soon out of sight.

I caught him 30 minutes later. He had his pack off and was kneeling in front of a heavyset woman in her mid-20s. Blonde hair, tattoos, flushed face. Two other young women were hovering nearby. One was holding a silver sun umbrella over the heavy girl. I realized I had seen Douglas stick that in his pack at the trailhead.

Douglas had his squirt bottle out and was gently misting her as he spoke.

“Deborah, I need you to take a deep breath,” he said quietly. “In. Hold it five seconds. Now out. Good. Again.”

I heard her inhale and exhale. I saw her shoulders tremble.

“I want to call my boyfriend,” the woman wailed. “I want to go home.”

“Breathe again, Deborah. In. Hold. Out.”

“Am I going to die?”

“Deborah,” he put a hand on each of her shoulders. “Look at me. Look at me. Not on my watch.”

Then: “Are you taking any medications?”

“Yes. For blood pressure. It’s HC… something.”

“Hydrochlorothiazide.”

“That’s it.”

“Deborah, that stuff is dumping salt out of your body. You need salt.”

Quavering. “OK.”

Douglas fished a water bottle out of his pack, tipped in some Liquid IV, gave it to her.

“Drink this.”

Then a bag of Goldfish.

“Eat these. All of them.”

After a few minutes the woman calmed, and her breathing steadied.

Douglas looked at her, then walked down the trail 30 feet. I followed him. Not too close.

He keyed his mic. “Dispatch, Papa 49.”

“Dispatch.”

“Dispatch, I am about 300 yards below the South Kaibab trailhead. I’m with a 26-year-old female with breathing problems. And she’s slipping a little into hyponatremia, possibly because of HCTZ she is taking. It’s mild. I’ve given her cooling, electrolytes, salty snacks. She’s recovering. I’ll stay with the patient at this location for 15 more minutes, then will walk her out.”

“Copy that, Papa 49. Any other assistance required?”

“Negative, dispatch. Papa 49 out.”

“Copy that. Dispatch out.”

At the top, Deborah turned to Douglas. “Thank you so much,” she said.

“You’re welcome. How are you feeling?”

“Better.”

“Good. Take it easy. Drink water, but only when you feel thirsty. Eat something salty.”

“I will.”

Douglas walked to the Ford and lowered its tailgate, tossed his pack and vest into the bed, then hopped up to sit and take off his boots. To my relief, he opened a cooler and handed me a cold Coke.

He patted the tailgate. “Sit.” I did.

“What is hypona…” I tried to ask.

“Hyponatremia. Her sodium levels dropped too low. It can kill a person. But she had a very light case.”

“Oh gosh!” This volunteer work was complicated.

I was sitting next to his mesh vest. I picked it up and made a show of rummaging through its pockets.

“What are you looking for?”

“My dignity.”

Three hours later, we were back in camp. I cooked dinner – chicken cutlets, sauteed broccoli – while Douglas perched at the dinette with his laptop and tapped at the video he still was editing.

After dinner, we sat by a fire.

I looked at him. “You didn’t seem flustered on the trail. With all those people stopping you – it was if you knew in advance what they would need. And that girl who was panicking. You calmed her when I thought she was about to lose it.”

He shrugged. “I do what’s in front of me. Ninety percent of it is just being willing to help.”

“And the radio? Where did that voice come from? I’ve never heard it from you. Like you were on a TV show. I know you stutter a little – you didn’t then.”

“It’s an extra voice. An act.”

“And you seem to understand people who are hurting.”

“Maybe.”

“Why?”

“I’ve been hurt here myself.”

“You have?”

“Yeah. Four years ago. Lyn and I were doing a big loop hike downstream of here. We were hiking along the Colorado – more of a route than a trail, really – and I tripped over a rock. Head-butted a boulder on the way down.”

He lifted his ball cap. The firelight revealed a faint U-shaped scar. I had noticed before, but not thought much about.

“Twelve stitches and a concussion. Plus I got a free helicopter ride out of the canyon.”

“Douglas! You could have been badly hurt!”

Another shrug. “I suppose. Hard head.”

“I guess so.”

“The good news was that the paramedic who fished me out, James, was married to Meghan. My boss here. She got me into PSAR.”

“Small blessings, I guess.”

He sipped bourbon while I had some white wine. Not a lot of talking, just the crackle of the fire. I thought about the scar on his forehead. It brought him here. Made him better with people.

I leaned into him. Clutched his arm.

In that moment, it was all I needed.

Love how the vest goes from punchline to lifeline without being heavy-handed about it. The Deborah scene hits perfectly, watching Doug shift from casual helper to someone who knows exactly what panic looks like and how to short-circuit it. I worked seasonl in Yosemite years back and saw so many people who looked over-prepared until someone needed help. That scar backstory tho, explains everything about why he's so attuned to people struggling.